Concerns raised about older adults mixing prescription drugs and herbal remedies

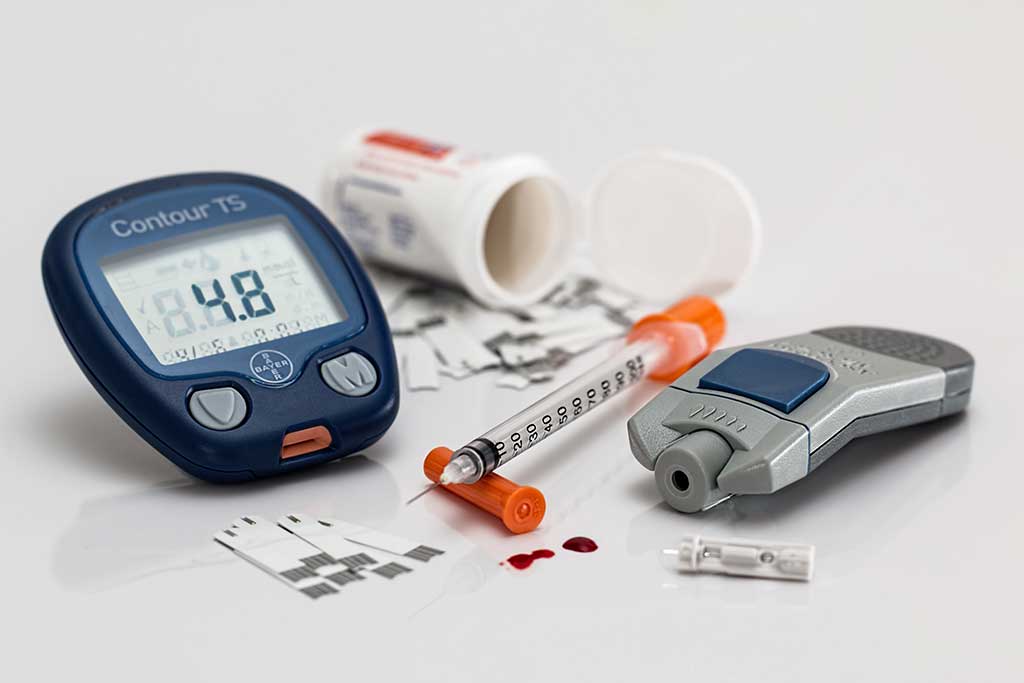

Medication

'More than a million over-65s may suffer dangerous side-effects because they are taking herbal remedies and dietary supplements alongside drugs prescribed by their GP' the Mail Online reports

"One million over-65s could be suffering dangerous side effects from mixing 'hazardous' combinations of drugs and herbal remedies, study warns," reports the Mail Online.

This follows a postal survey of 149 adults aged 65 and above from southeast England. The survey wanted to see whether people were choosing to take herbal or dietary supplements while also taking prescription medication. All respondents were taking at least 1 prescription drug, and a third of them were also taking some kind of supplement.

Most of the combinations were not harmful, but the researchers did find some people taking combinations that were potentially harmful.

These included:

- a class of blood pressure drug (calcium channel blockers) with the herbal remedy St John's wort, which may reduce the effectiveness of the blood pressure drug

- the type 2 diabetes drug metformin with glucosamine, which may affect blood glucose control

- another blood pressure medication bisoprolol with omega-3 fish oil, which may further reduce blood pressure

The study gives an indication of how common supplement use is, and in some cases raises concerning patterns. However, it was a very small study and it is difficult to know whether the results would generalise to the wider population. There may be other drug-supplement interactions that were not found in this small group, but which might exist in other populations.

Some people mistakenly think a treatment or supplement marketed as "herbal" means it does not cause any side effects or drug interactions.

If you are unsure whether it is safe to take a supplement with your prescribed medication, read the leaflets provided with both medicines, or talk to your pharmacist or GP.

It's worth noting that these sorts of drug interactions can affect people of any age, not just people aged over 65.

Read more NHS advice about herbal remedies.

Where did the story come from?

This study was carried out by researchers from the University of Hertfordshire and NHS Improvement. The study did not receive any funding. It was published in the peer-reviewed British Journal of General Practice.

The UK media generally covered the story fairly well, although the headlines tended to focus on the estimate that more than a million people could be affected. This figure is uncertain as it was based on a very simple calculation scaling up from a small study.

Also, many of the papers used the phrase "alternative medicines", when some of the substances studied in this research were actually commonly used food and vitamin supplements.

By talking about alternative medicines, people might not realise that this study is relevant to them, as they may have a different understanding of that phrase.

What kind of research was this?

This was a cross-sectional survey, which means that a group of people were studied at a single point in time. This kind of study has the benefit of being relatively simple and quick to carry out. It's also a good way to look at how common something is (like use of herbal supplements) at a particular time.

However, cross-sectional studies can't tell us much more than this or explore the reasons behind observed patterns. We don't know the details of why people were taking drugs and supplements at the same time, for how long they had done this, and whether this had caused problems for them. Also, studies need to include a large and random cross-section of the relevant population to be able to give a reliable estimate of how common something is. So this small localised study may not be truly representative.

What did the research involve?

Between January and April 2016, this study mailed questionnaires to 400 older adults who were not living in care homes. Some were from a GP practice based in a rural area of Essex with a mainly white population. The others were from a GP practice in an area of London with a higher proportion of people from black, Asian and other minority ethnic groups.

Eligible participants were randomly selected people aged 65 or over who were taking at least 1 prescription medication. People with dementia, those who were terminally ill, and those who would not be able to consent to participate were excluded.

The questionnaire asked people what prescription drugs they were taking, as well as what "herbal medicinal products" or dietary supplements they might also be using. The questionnaire included examples of common herbal products (such as St John's wort or gingko) so that people understood what might be included in that category.

The researchers used a database to check whether people were taking any combination of prescription medicine and herbal remedy known to be potentially harmful. They labelled each interaction according to the following criteria:

- action: whether it needed action or not

- severity: how likely it was to cause a problem for the patient if the situation was not managed

- evidence: how good is the evidence around the interaction

Reminder letters were sent after 2 weeks, and further questionnaires were then sent to people who hadn't previously responded. In total, 149 people responded and could be included in the analysis.

What were the basic results?

People were taking an average of 3 prescription drugs on a regular basis, with the most common including statins, beta-blockers and calcium channel blockers (used in the treatment of heart conditions and high blood pressure) and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs).

Around a third (33.6%) of the people in the study were using herbal remedies or supplements alongside their regular medications. This rate was higher in women (43.3%) than men (22.5%). People who were using herbal remedies or supplements were taking just 1 on average, though some people took as many as 8.

Most of the people (78%) who took supplements alongside their prescribed medication were taking vitamin and mineral supplements including cod liver oil, multivitamins, vitamin D and glucosamine.

They found 20% of people were using herbal products only. The most common were evening primrose oil, valerian, Nytol Herbal®, and garlic. Just over half of the reported potential interactions were considered to not be of clinical significance. However, 21 combinations were identified as having uncertain consequences, and 6 were considered potentially hazardous or significantly hazardous.

The combinations considered particularly risky were:

- the supplement Bonecal with levothyroxine (medicine for an underactive thyroid); the calcium in Bonecal reduces the effectiveness of levothyroxine

- peppermint taken with the medicine lansoprazole (which lowers stomach acid) – the medicine may affect the protective coating of peppermint capsules, which could lead to side effects caused by the peppermint

- St John's wort with the blood pressure drug amlodipine, which may make the drug less effective

- the supplement glucosamine with metformin (a diabetes drug), a combination that may affect blood glucose control

- omega-3 fish oil with the blood pressure drug bisoprolol, which can lower blood pressure too much

- the herbal remedy gingko with the stomach acid drug rabeprazole – this makes the drug less effective

How did the researchers interpret the results?

The researchers noted that if their study was representative of the population as a whole, then potentially 1.3 million older adults in the UK might be at risk of at least 1 herb-drug or supplement-drug interaction. They suggest GPs should routinely question the use of herbals and supplements among older adults.

Conclusion

This study gives us an interesting snapshot into the habits of a group of older adults who are using supplements alongside their prescription medications.

But we don't know how representative this study is of the wider population of older adults in the UK. The study includes patients from only 2 GP surgeries in southeast England. Although the researchers chose practices with different population characteristics, the people in the study might not be representative of the country as a whole.

The study was also very small, at just 149 people. We don't know anything about the people who did not participate. For example, it may be that these people were more likely to be users of herbal remedies and didn't want to share this information with their doctor. Or they might not have used herbal remedies at all and didn't think the study was relevant to them. Either way, this could affect the results and mean the study is not representative.

Finally, the study did not explore the reasons why people were taking supplements or herbal products alongside prescribed drugs, for how long they had done this, and whether they were aware of potential interactions. We also don't know whether there were any actual side effects or harms reported by the people in the study.

If you are unsure whether it is safe to take a herbal remedy or supplement along with your regular medication, talk to a pharmacist or your GP. It is also a good idea to do this if you are taking a lot of different medications that have been added to your prescription over the years, or if you are unsure what any of your medications are for.

Subscribe

Subscribe Ask the doctor

Ask the doctor Rate this article

Rate this article Find products

Find products